SWIM for Implementers

Maintaining an accurate picture of the membership of a distributed network is tricky. Machines fail and communications between them fail. Distributed computing is hard in part not just because these things happen but because it can be difficult to tell when they do. A machine can only ever have current information about itself; its view of the network is cobbled together from information that might be obsolete by the time it arrives. So in order to keep a distributed network cohesive, its members must constantly check in on each other: “Are you still there? I’m still here.”

Clever minds have expended considerable effort contending with these challenges by developing strategies that carve out compromises between a few important efficiency criteria:

- failure detection time—how long it takes any member to recognize another member’s failure,

- false positive failure rate—how often a functioning member is declared to have failed, and

- network load—how much traffic the members need to keep up with.

The Scalable Weakly Consistent Infection-Style Process Group Membership (SWIM) Protocol is one such approach. Originally published in 2002, it was designed as an alternative to the traditional heartbeating paradigm of membership maintenance and failure detection, in which each member periodically announces its health to the entire network. This method is simple in principle, but it scales poorly because the message load increases quadratically with network size.

As implemented according to the paper (in this article I’ll include all of the “extensions” discussed in section 4), the SWIM protocol is fully decentralized and disseminates membership information throughout the network without multicasting, exclusively via gossiping between members—”infection-style”—with an expected constant packet rate per member. It also provides for detection of failed members in expected constant time, with latency in the propagation of membership information growing only logarithmically with network size.

While the paper gives a comprehensive treatment of the theory and properties of the protocol and the guarantees it offers, its terminology is inconsistent and I found its discussion of implementation details patchy and imprecise when I was first considering writing an implementation of my own. I hope the following will fill in the gaps.

A little help from my friends

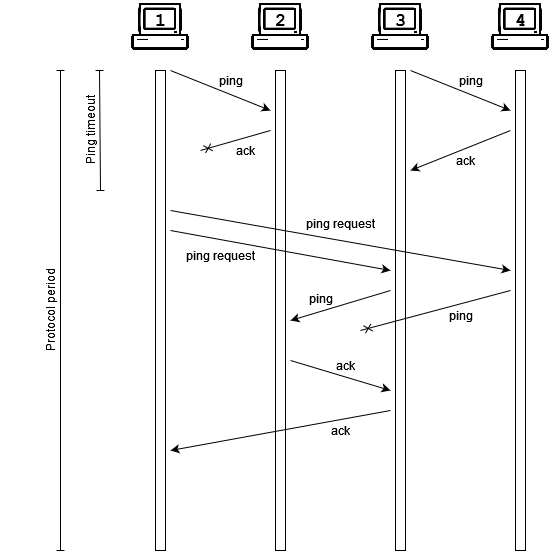

The core of the SWIM concept is that nodes regularly exchange UDP packets to check up on each other and simultaneously exchange piggybacked status messages to disseminate shared knowledge of the network membership. Each node periodically chooses another node in its membership list to send a ping to, and includes within the packet a number of messages describing its current understanding of the status of other nodes. When a node receives such a packet, it sends back an acknowledgement packet carrying some messages of its own.

// A packetType describes the meaning of a packet.

type packetType byte

const (

ping packetType = iota

pingReq

ack

)

// A packet represents a network packet.

type packet struct {

Type packetType

remoteID id

TargetID id // for ping requests

Messages []*message

}

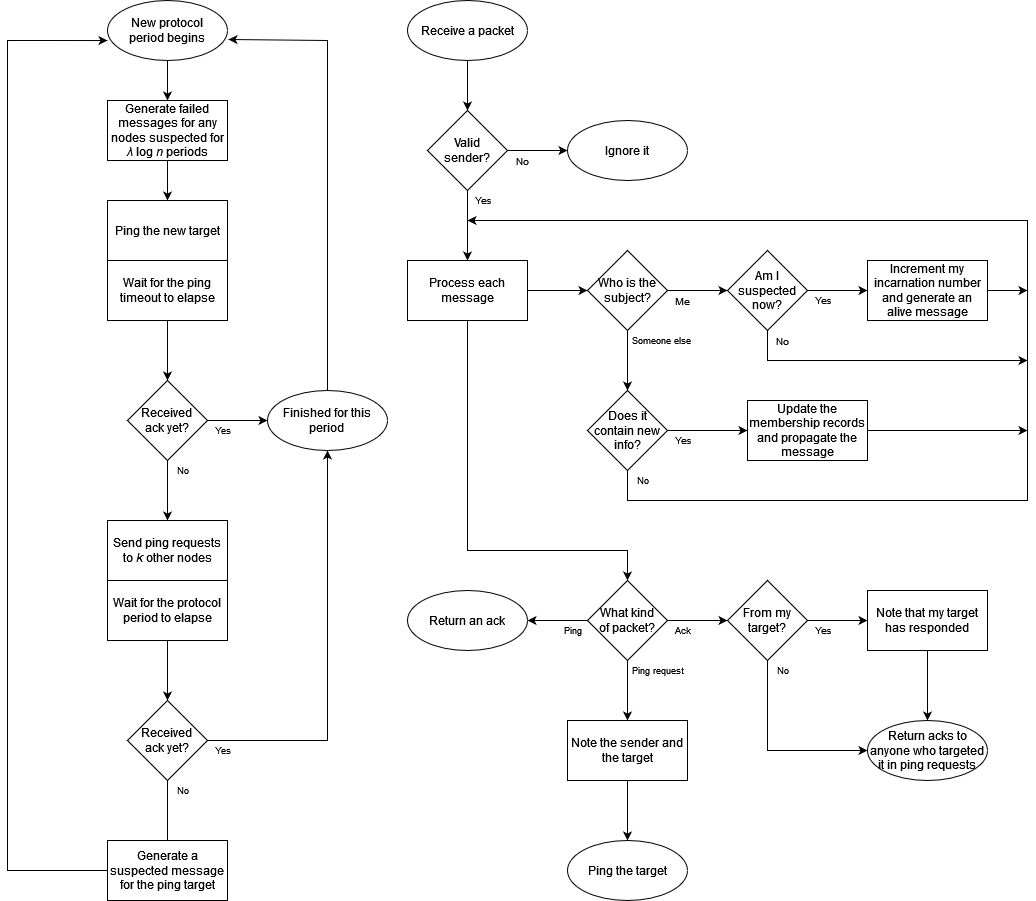

Of course, the whole reason for doing all of this is that lots can go wrong along the way: the network connection might be faulty, the packet might be dropped, or in the worst case, a properly delivered packet might never be received because its intended recipient has crashed. So if no ack is received within a preset timeout duration, the node sends ping requests—so-called “outsourced heartbeats”—to some other nodes to ask that they ping the target and report back. If there’s still no response by the end of the protocol period, the node can suspect with some confidence that its target has ceased participation in the protocol and communicate its suspicion throughout the network.

On suspicion

But false positives are often expensive, so suspicion is exactly what is communicated. Rather than declaring outright that its target has stopped working, a node circulates a message assigning its target the intermediate status of suspected. A suspected node is treated as functional for operational purposes, but it’s on the clock: after enough time has passed without hearing from it, any other node can declare it failed and boot it from the network.

// A status describes a node's membership status.

type status byte

const (

alive status = iota

suspected

failed

)

// A message carries membership information.

type message struct {

NodeID id

Status status

Incarnation int

}

How long is long enough? The answer grows logarithmically with the number of nodes. A derivation based on an epidemic model of n homogeneously mixing members, one of whom is “infected”—in this case, with a newly generated status message—concludes that in the limit of large n, the number of members that remain uninfected (ignorant of the message) after λ log n rounds of transmission approaches n-(2λ-2). Setting λ > 1 therefore ensures that each message is disseminated to the entire network with high confidence.

So λ log n is the number of protocol periods a node waits before declaring a suspected node failed. It’s also how many times each node should send each message it has learned, prioritizing messages that have been sent fewer times so that fresh status information makes it out onto at least a portion of the network promptly.

I’m still here

How can a node clear its name after discovering that it has been marked suspected? Simply publishing an alive message about itself isn’t sufficient, since packets can be delayed and may not arrive in chronological order. Instead, in order to demonstrate that a node’s assertion of liveness overrides the current suspicion, a total ordering of some kind is required.

To this end, each node maintains a monotonic counter that the paper calls its incarnation, which only the node itself can increment, and each message carries the incarnation number of its subject. When a node receives word that it has been declared suspected, it increments its own incarnation and starts sending an alive message with the new value.

A node marked failed has no such recourse. A failed message takes precedence over all others, and its effect is irrevocable: as soon as node i receives a failed message about another node j, i deletes j from its membership list and ignores any future packets received from j and any subsequent messages regarding j. Eventually this information will propagate throughout the network, and j will find that it has no more SWIMming partners.

This, then, is the total ordering of messages by status and incarnation: alive0 < suspected0 < … < aliven-1 < suspectedn-1 < aliven < suspectedn < aliven+1 < suspectedn+1 < … < failed.

// supersedes reports whether a supersedes b.

func supersedes(a, b *message) bool {

if b.Status == failed {

return false

}

if a.Status == failed {

return true

}

if a.Incarnation == b.Incarnation {

return a.Status == suspected && b.Status == alive

}

return a.Incarnation > b.Incarnation

}

Configurable parameters

Besides λ (the “thoroughness coefficient”?), there are a few more parameters that can be tuned to the application’s specific requirements:

- tp, the protocol period duration,

- tto, the ping timeout duration, and

- k, the number of ping requests to generate.

Before the paper starts talking about the suspicion mechanism, it goes into detail on how these parameters influence the properties of failure detection time and false positive rate.

Let tf be the failure detection time required by the application (that is, the average interval between when a node fails and when any other node begins to suspect its failure). If a fraction q of the nodes are non-faulty, the chance of any arbitrary node being chosen as a ping target during a protocol period approaches 1-e-q for large networks, and so the protocol period should not exceed

tp ≤ tf(1-e-q).

Note that this value does not depend on the size of the network, a reflection of the fact that each node can expect on average to be the target of one ping per protocol period.

On the other hand, the protocol period’s length does have a lower bound: it has to be long enough to complete all communications that might need to take place. Define the ping timeout duration to be the amount of time to wait for an ack before sending ping requests. To compromise between overall network protocol latency and the volume of ping requests, it should be chosen as a high-percentile cutoff value over the amount of time a round-trip communication between any two nodes is expected to take. The protocol period must be at least three times as long as this, to allow sufficient time for pings to come back, and then for ping requests and their responses if necessary:

tp ≥ 3tto.

Speaking of ping requests, let r be the fraction of packets that are delivered without delay and pfp be the false positive probability that the application is willing to tolerate (that is, the chance that a node declared suspected is in fact healthy). The number of ping requests that must be sent out to satisfy this requirement is

k ≥ log(pfp/q • (1-e-q)/(1-r2)) / log(1-qr4).

As an illustration, for a 95% package delivery rate across a 95% functional network in an application requiring a false positive rate less than 1%, k comes out to just 1.83. And again, this is before the paper even mentions the suspicion mechanism. (The paper does not reanalyze these parameters in the context of being able to declare a node suspected instead of simply ejecting it outright.)

Strong completeness

One more basic property that membership protocols tend to highly prioritize is strong completeness: eventually, every failed member is recognized as failed by every healthy member. Choosing ping targets completely at random does not ensure this, as the interval between successive pings to any particular target is unbounded—in fact, for any pair of nodes, there is no guarantee that either will ever ping the other.

Instead, the protocol employs a specific target selection mechanism to enforce some regularity: randomized round-robin ordering. Each node maintains a shuffled list of the other nodes it’s aware of and advances through the list to choose each protocol period’s ping target, shuffling when the list is exhausted. In order to avoid biasing the end of the list toward recent additions, whenever a new node is encountered, it’s inserted into the list at a random position. For a list of n nodes, this mechanism provides an upper bound of 2n-1 protocol periods between successive pings to the same target, satisfying the strong completeness criterion.

And, excluding the business of actually sending and receiving packets over the wire, those are all of the synchronous components of the finite state machine core of a SWIM node:

- a unique ID and incarnation number

- a list of other working nodes and their statuses (incarnation and whether suspected)

- a list of removed nodes to ignore

- an ordered list of working node IDs to iterate through for ping target selection

- a list of incoming ping request senders and their targets

- a priority queue for messages, each to be sent out λ log n times or until superseded

My implementation has a newly created node launch two goroutines to manipulate its state: one to run the protocol period loop and another to process incoming packets.

A matter of professional courtesy

I’ve found it prudent to extend the protocol in one specific way that doesn’t impact any of the bounds or guarantees the paper focuses on: when a node declares another node suspected or failed and begins propagating a message to that effect, it also fast-tracks a supernumary ping carrying just that message directly to its subject. In the case that a healthy node is suspected, this might help to curtail the period of suspicion and thus further reduce the chance of a false positive brought on by a particularly unfortunate pattern of message propagation.

If, in spite of all of the above, a false positive does occur, this will at least enable the node in question to decommission its resources and inform its parent application without having to spend λ log n protocol periods wondering why it’s observing the extinction of its network traffic. This might not make a big difference most of the time, but it seemed like a considerate thing to do.

It also neatly manifests the essence of distributed network maintenance: “I’m still here. Are you still there?”