Small Steps for Cleaner Code

It’s no secret that frequent small commits are a hallmark of good coding practice. (The day I was taught this was the day GitHub became useful.) There are many reasons for this, most having to do with the fact that version control tools can help in proportion to the resolution they offer into a repository’s history.

But another practical benefit for the conscientious coder is that building incrementally can have a powerful paring effect on the complexity of the resulting code. I ran across a striking example of this in a recent project.

A case study

Module cassino is an engine to administer the card game of the same name. I’d been thinking off and on about illustrating the game in code because it seemed like a fun exercise and potentially an interesting challenge to write a good AI player for. Much of the game’s human appeal as an idle afternoon pastime lies in the simplicity and intuitiveness of its rules, and its modest scale: even at a leisurely pace, players familiar with the rules can easily complete a game inside of 10 minutes. As such, I was particularly interested to see how simple and elegant the code could be.

Sure enough, this project turned out to be a perfect opportunity to enjoy working through a small-scale case study in how the practice of incremental development itself can bake simplicity right into the architecture.

Build and capture

This post will track the development of a hypothetical Action type that can unambiguously describe all possible actions that a player can take on their turn. It’s not essential to understand all of the rules in order to follow along, but here’s an overview for the curious, in 99 words:

A turn consists of playing a card from the player’s hand by either trailing it (laying it face-up on the table) or using it in a build or capture. A card can capture any cards on the table of the same rank, or, in the case of number cards, any combination of cards or single-set builds whose values add up to the capturing card’s rank. Building is the act of combining number cards, possibly multiple sets of them, into a pile that can be captured later (by either player) with a card whose value equals their sum.

Depending on the cards on the table and in a player’s hand, there can be quite a few possible courses of action. The challenge is to find a clear and concise way to represent them all. A few useful invariants are woven through the options, including:

- Each turn involves playing exactly one hand card

- Cards only leave the table by being captured

- Number cards are only combined when captured or involved in a build

- A pile of cards on the table is a build precisely when it has two or more cards

- Builds are indivisible

- Builds do not include face cards

- Each set of captured number cards has a total value equal to the capturing card

- Each set of cards in a build has a total value equal to the build’s value

- The value of a build may change precisely when there is only one such set

Many small steps

A top-down strategy for designing an Action type to unambiguously describe all possible player turns could begin by trying to satisfy all of the above criteria, and the result would doubtless be useful in any form. But it might carry some unnecessary complexity. In contrast, here’s what it looks like built from scratch.

Level 1: Trailing

Let’s play a game. The only thing you can do on your turn is choose a card from your hand and put it on the table. But you do get to choose:

type Action struct {

Card Card

}

We’ll keep an eye out for cases that render the input invalid. So far, there’s only one:

- Card is not in the player’s hand

This game is extremely trivial. It’s only slightly more dignified than a cooperative version of 52 Pickup. But it’s a start.

Level 2: Capturing

In order to implement capturing, an Action needs to be able to describe which cards are to be captured. For now, that’s as simple as a slice of Cards.

type Action struct {

Card Card

Capture []Card

}

New invalid cases:

- A card in Capture is not on the table

- The same card is listed more than once in Capture

- A card in Capture doesn’t match the hand card’s rank

Match a card in your hand with a card on the table, and you can keep them! Slightly less trivial, but still boring. But at least not every game will end in a scoreless draw now.

Level 3: Combining captures

As a prelude to building, the next step is to allow captures of combinations of cards that add up to the value of the capturing card, and indeed even multiple such combinations. For example, if there is a 2, a 4, a 5, and a 7 on the table, a player can capture all of them at once with a 9.

The Capture field could remain a []Card, but that would give the engine the task of distinguishing between valid captures like the one above and invalid ones that add up to the same total, like an ace, a 4, a 6, and a 7. The Player can handle the burden of demonstrating that a proposed capture consists of valid subsets, so the engine will codify this by changing the type to [][]Card, and require that the elements of each []Card add up to the capturing card’s value.

type Action struct {

Card Card

Capture [][]Card

}

Invalid:

- A set of number cards doesn’t add up to the hand card’s rank

- A face card is in a set with any other card

Here at last is a game that kindergarteners could enjoy for a while. But it’s time to start the steepest part of the climb.

Level 4: Non-additive building

It’s time to build. The smallest step to start with is a restrictive form of compound building that preserves a convenient assumption we’ve been able to rely on so far with capturing: that the value of the hand card is equal to the value of the pile(s) it’s played onto. So we’ll get the structure of compound building into place first and leave the mechanics of simple building, which turns out to involve a bit more heavy lifting, for later.

Speaking of assumptions, this pattern of the Action type’s increasing complexity is a direct consequence of the fact that each step has involved violating what had previously been a valid assumption about the gameplay. Level 2 introduces the idea that cards can be removed from the table, level 3 that cards can be removed in combinations by a card of a different rank. At level 4, cards can now be combined and remain on the table. So the fundamental element of table constituency must now be a type that can describe any number of cards together. Call it a pile.

A pile contains cards and has a characteristic value. It’s possible to encode this value in the structure used to store the cards, but the code is easier to read if we make it a separate field of the pile struct for convenience. It will also be convenient for each pile to have a unique ID. Finally, to enforce the rule that a player who last played onto a build cannot trail (to buy time and force a powerless opponent to reveal the rest of their hand), it’s necessary to track who controls a build, and it’s as easy to do that within each Pile as anywhere else.

type Pile struct {

ID ID

Cards []Card

Value int

Controller int

}

As for our Action, it must now specify piles to capture rather than individual cards, of course. But there’s the additional matter of how to encode building actions. So far, their structure is substantially identical to captures: one or more sets of cards (now piles) whose total value equals the value of the hand card—a [][]ID. The only practical difference is that the cards remain on the table in one case and in the other they’re removed. And whenever it’s possible to build, it’s also possible to just capture. The Action type needs a way to disambiguate the Player’s intent. One option would be to have separate Capture and Build fields, and check an additional restriction that at most one of them is populated. But there is a simpler and sturdier way: with “Capture” suitably renamed to cover both capturing and building, a boolean will suffice.

type Action struct {

Card Card

Sets [][]ID

Build bool

}

Invalid:

- Invalid pile ID

- A build or capture includes a set with a wrong value

- The player builds without holding a card of the build’s value

- The player captures with their last card of the value of a build they still control

- The player trails while they control a build

- Card or Sets contains a face card when Build is

true - A compound build is in a set with any other pile

This is starting to feel more like it could turn out to be a substantial game, but it still lacks nuance. The last step the tallest.

Level 5: Additive building

Now it will be possible to create a build of a value that is higher than the value of the hand card. An Action needs to be able to identify a group of piles to combine with the hand card, so a []ID. But that group is not a complete set by itself because it doesn’t equal the total value of the pile until the hand card is added into it. I went back and forth on what to call this new field before eventually settling on Add as good documentation.

type Action struct {

Card Card

Add []ID

Sets [][]ID

Build bool

}

Invalid:

- A compound build is used in Add

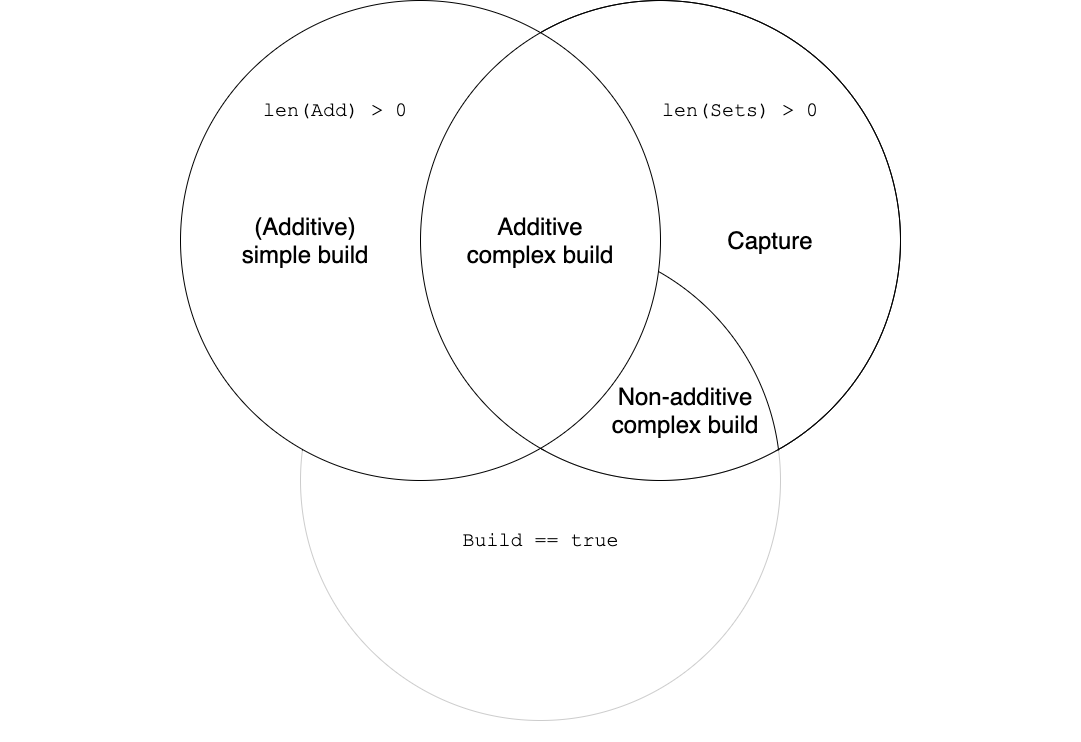

This single addition also realizes the fully generalized building mechanic: a complex build that also contains an added component. Note that the Build flag is still necessary to disambiguate compound builds with no added component, but the act of building is now a superset of both: an Action creates a build if Build is true or Add is non-empty.

But not all piles can be used in Add to make a simple build: conceptually, only piles whose values can change are eligible. A compound build has a fixed value, since it’s composed of more than one set. So only single cards and simple builds can be added, and the final requirement is that a Pile that represents a build needs to be able to report whether it’s simple or compound.

type Pile struct {

ID ID

Cards []Card

Value int

Compound bool

Controller int

}

And those two types are enough to facilitate the full functionality of the game.

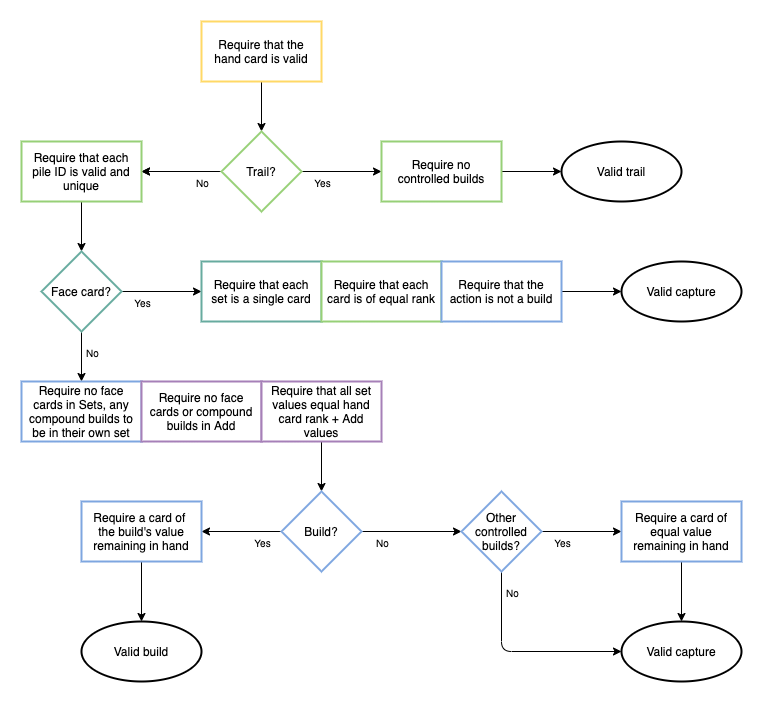

Along the way, we’ve noted ways that an Action might be ill-formed or impermissible. Letting the tests write the code, here’s what a validateAction function might look like:

Analysis

This is a tractable example of code that ends up concise as a direct result of the process used to develop it. The importance of this practice is time-honored wisdom for many other good reasons, of course—code written one step at a time, one goal at a time, is eminently more modular and reviewable, both of which contribute directly to its maintainability.

Another important but less noted benefit, though, is the bonus to its lower-level readability: for very little extra effort, one ends up with structure whose purpose is clear at a glance. This payoff is on par with that of other best practices like sound documentation and naming. By my reckoning, this kind of lean form-follows-function code shape is one of the biggest advantages of building through minimal incremental changes.

This is important for me to remind myself, because left to my own devices, I tend to prefer starting my workflow with a more or less complete rough sketch of the important pieces of the codebase. It’s useful as a bridge from planning and prep work toward a minimal working implementation, and as an opportunity to look ahead and consider edge cases and critical paths. Perhaps it also contributes to a kind of security blanket effect of feeling prepared for the real work.

But the siren song of “While I’m at it…” requires constant vigilance to prevent unnecessary complexity from spiraling. And once that real work is underway, the utility of the blueprint sketch tends to be short-lived: every so often along the way, I invariably run across some aspect of envisioned functionality that in fact my data structures just Aren’t Gonna Need. And that’s a good thing. On the other hand, I’m happy to embrace what might be coldly calculated as the inefficiency of this approach: more often than not, it’s at least a learning experience.

All in all, though, there is no substitute for constructing every piece of functionality as individually and independently as possible. The cost is a measured pace demanded by mindfulness at every step in minimizing technical debt.

In the long run, of course, that tends to compare well with the alternative.