A Concurrent Sudoku Solver with Channels

Logical deduction puzzles like sudoku can often be modeled as consisting of a large number of similar and independent deductive steps, making them amenable to concurrency-based implementations. Sudokami is a concurrent sudoku solver written in Go, a sketch of some of my ideas along these lines. Here’s how it works.

Just Go Things

The unit of concurrency in Go is the goroutine, which is an independently executing function with its own call stack—somewhat akin to a thread, except that goroutines are managed directly by the Go runtime itself. They’re cheap too: Sudokami creates more than a thousand of them, which barely taxes the runtime’s capabilities.

Goroutines communicate with each other via channels, on which one goroutine can send a value to be received by another. Channels can optionally be declared with a buffer size. Unbuffered channels enforce synchronicity by blocking a receive operation <-ch if no incoming send operation ch <- v is ready. This is the basis of Go’s synchronization functionality. On the other hand, buffered channels will only block sends if the buffer is already full, in a manner similar to Erlang’s mailboxes. The select statement provides a way to maintain synchronicity when using multiple channel operations concurrently, or a single channel if the select contains a default clause. With a single channel outside of a select, however, the question of whether to buffer reduces to a tradeoff of enabling synchronization vs. avoiding blocking.

The exception to this is that receives on a channel will never block if that channel has already been closed. Calling close(ch) will cause subsequent receives on ch to succeed immediately with the zero value of ch’s type (after the contents of its buffer, if any, have been depleted). Many concurrency idioms in Go rely on this helpful feature, but here too there is an important caveat: whereas a receive on a closed channel always succeeds, a send on a closed channel causes a run-time panic. Idioms based around closing a channel are therefore generally restricted to communication designs in which the channel has at most one goroutine sending on it. (The implementation below relies instead on a pattern of each channel having many senders but only one receiver, so close is never called.)

The Logic of Sudoku

Sudoku is a logical constraint puzzle in which a 9×9 grid of “cells” must be filled with the digits 1-9 such that each digit is unique in its row and column, and also in its 3×3 “box” subdivision of the grid. It is thus a type of exact cover problem.

But the basic structural unit of a sudoku puzzle is not the cell, and the basic logical unit is not the digit. A cell can be in nine possible states, exactly one of which is shown to be true in the unique solution of a well-formed puzzle. Sudoku aficionados often use the term “pencil mark” to describe each of a cell’s possible solution states. Below, they are called candidate inferences or candidates. A sudoku puzzle has 93 of them—one for each unique combination of row, column, and digit—and they are all boolean in nature: each one can be true or false. This subtle reformulation of a digit in the range [1, 9] as a collection of nine mutually exclusive boolean values allows the structural encoding of the logic underlying the puzzle to be refined and generalized.

A cell, then, can be described as the intersection of one row and one column, and it contains nine candidates, each corresponding to a digit. Extending the pencil mark analogy with erasing all but one possible digit to determine the state of a cell, we may consider the instances of a particular digit in a particular row. Here too, there are nine mutually exclusive possibilities, one for each column. Likewise for all instances of a particular digit across any row in a particular column. In a sense, a sudoku puzzle is a 9×9×9 cube of these boolean candidate inferences, and solving the puzzle is the act of determining which 81 of them are true.

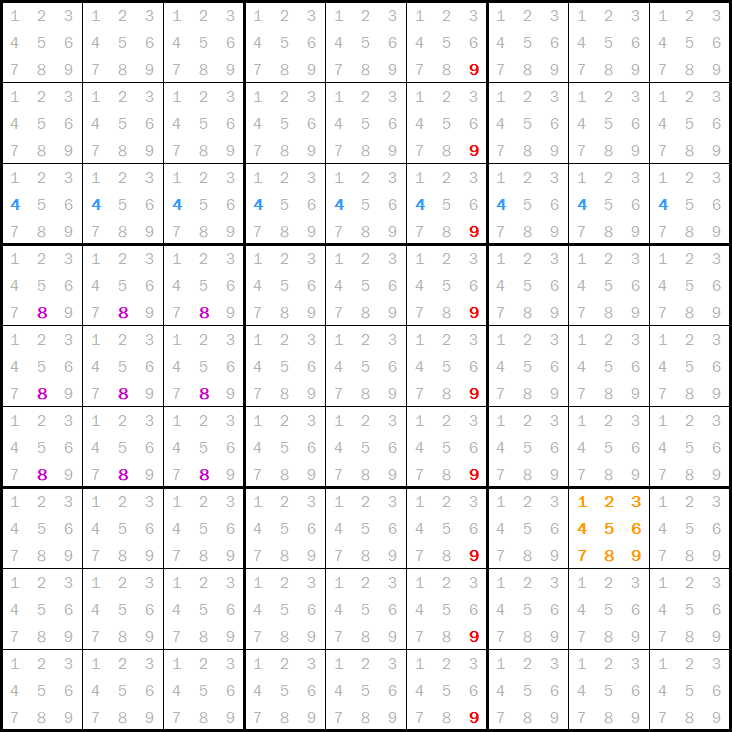

Call a complete set of mutually exclusive candidates a group. “The 6s in the top row” is a group. “The 8s in the bottom right box” is too. So is “all of the digits in the 2nd column of the 5th row”. Here is a grid with a few (non-intersecting) groups highlighted:

Each group contains exactly nine candidates, and each candidate belongs to four groups:

- its cell

- the instances of its digit in its row

- the instances of its digit in its column

- the instances of its digit in its 3×3 box

Given this definition, the logic of solving a sudoku puzzle can be fully described in terms of groups and their candidates, without any direct reference to locations within the grid, rows, columns, boxes, cells, or even digits.

(NB: The term “group” is often used in popular sudoku literature to describe any row, column, or box in general; under this usage, the “One Rule” is more succinctly stated as “Each digit appears once in each group”, but that might be its only advantage—in particular, it’s worth noting that each of these “groups” can be in 9! possible states. The definition above is more logically elemental and also more useful to code with, as it exposes the helpful abstraction that a cell is the same kind of constraint domain as, for example, a row-digit intersection.)

Data Structures

How might these entities function in code? A Group object could watch its Candidates to figure out when one Candidate must be true, and then advise its other Candidates accordingly. Each Candidate might attempt to determine whether it was true, and then communicate that information to its Groups. (In view of the bipartite nature of exact cover problems, we would hope to design a communication protocol obviating the need for Candidates to communicate directly with each other.) To an extent, the Candidate and Group types would have symmetrical definitions: each would need to receive from a channel on which its counterparts would send, and be able to send on some channels from which each of its counterparts would receive. So the their definitions might look something like this:

type Candidate struct {

ch chan bool

groups []chan bool

value bool

}

type Group struct {

ch chan bool

cans []chan bool

}

Locally, each Group would additionally need to keep track of the information it receives. In practice, however, the number of falses is sufficient, and since this number is only used within the scope of the Group’s goroutine, a separate field for it is not necessary. On the other hand, in order to display the finished solution, each Candidate must also remember its truth value.

A few design goals:

- First and foremost, deadlock must be provably impossible in the process of solving a well-formed puzzle with a unique solution.

- In the spirit of logical simplicity, Candidates and Groups should carry minimal information about their location within the puzzle, so that their function can be as decentralized as possible. The necessary relationships are encoded in the set of channel references each possesses. Beyond this, the logical symmetry of the puzzle does not strictly require any positional information to be considered, as there are no “special” rows, columns, or digits.

- It would be nice to limit the number of values that would need to be sent. Specifically, is it ever necessary for a Candidate to send more than one value to each of its Groups? Can a Group function properly sending only one identical value to each of its Candidates?

- For the sake of readability and reasonability, it would also be nice to limit the number of channels involved. Will one per Candidate and one per Group work?

It seems that an ideal design solution would have one channel for each Candidate and one for each Group, on which they listen for information sent by their counterparts. Each Candidate should send to each of its Groups exactly once in the course of the solution process, without needing to indicate its location in the puzzle. Each Group should send to each of its Candidates exactly once, without needing to know their location. Since a Group receives all of its Candidates’ information on a single channel, this last criterion necessitates that it send the same boolean value to all of its Candidates.

It turns out that there is a logically consistent and relatively simple way to do all of this.

Communication Protocol

In designing the protocol by which Candidates and Groups interact, we make use of the fact that, in a properly formed sudoku puzzle with a unique solution, the truth value of a Candidate does not depend on the order of the deductions that imply its truth or falsity. For a hypothetical protocol in which each boolean value sent to a Candidate indicated that Candidate’s truth value, it would receive the same information from each of its Groups, in some order or other. Therefore, it would only be necessary for each Candidate to pay attention to the first value it received. The above constraint can be relaxed accordingly: a Group may only send a value to a Candidate if that value indicates whether the Candidate is true, unless the Group knows that the Candidate has already received a value. Specifically, it’s fine for a Group to send false to all of its Candidates after it has received a value of true from one of them, since it will receive true exactly once in a well-formed puzzle, and the Candidate that sent it already knows that it is true (because it received this information first from another source). On the other hand, a Group must not send true until it has received eight falses.

These conditions strongly suggest the use of buffered channels. While concurrency is one of Sudokami’s central design goals, there is no need for Groups and Candidates to actually synchronize with each other. On the other hand, since the number of values that will be sent on each channel is known in advance, buffering to this capacity ensures that sends will never block, even if not all of those values are consumed.

The protocol itself is simple:

- Each Candidate listens on its own channel, in an anonymous function launched as a separate goroutine by the

gostatement. The first boolean value it receives informs it whether it is part of the puzzle’s solution. It sends this value to all of its Groups and then takes no further action on the additional values sent to it—in fact, it doesn’t even bother to receive them. The crucial invariant here is that a Candidate only sends a value to its Groups after it has already received a value.

func NewCandidate(wg *sync.WaitGroup) *Candidate {

c := &Candidate{

ch: make(chan bool, nGroups+1),

groups: make([]chan bool, 0, nGroups), // caller will populate

}

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

c.value = <-c.ch

sendAll(c.groups, c.value)

wg.Done()

}()

return c

}

- Independently, each Group listens on its own channel, keeping a count of how many Candidates might still be true. This number starts at 9 and is decremented for each

falsereceived.- If the number reaches 1, only one of the Candidates has yet to report in: the one that is true. Conveniently, it’s also the only Candidate still “listening”. So there will be no objections if the Group sends the single value

trueto all of its Candidates. - On the other hand, as soon as the Group receives a single

true, it knows that it can sendfalseto all of its Candidates: one of them (which is no longer listening) has learned that it is true, and all of the others must therefore be false.

- If the number reaches 1, only one of the Candidates has yet to report in: the one that is true. Conveniently, it’s also the only Candidate still “listening”. So there will be no objections if the Group sends the single value

func NewGroup() *Group {

g := &Group{

ch: make(chan bool, nCan),

cans: make([]chan bool, 0, nCan), // caller will populate

}

go func() {

for n := nCan; n > 1; n-- {

if <-g.ch {

sendAll(g.cans, false)

return

}

}

sendAll(g.cans, true)

}()

return g

}

As an aside, the code above illustrates a common pattern for struct values whose utility is predicated on concurrent execution: launch a goroutine to manipulate it from inside the same function that allocates storage for it. (If that value isn’t useful without the goroutine running, then the New function is an appropriate place to launch it from.)

A NewGrid function creates the Candidates and Groups and connects them together by giving each one references of its counterparts’ channels, and the whole contraption is set in motion by a Clue method that sends the puzzle’s initial clues as true values to the corresponding Candidates. Then all of the dominoes fall as logic dictates they must. A WaitGroup ensures that the solution process runs its course before displaying the result.

func main() {

in := os.Args[1]

s, err := parseInput(in)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

var wg sync.WaitGroup

g := NewGrid(&wg)

for i, n := range s {

if n != 0 {

g.Clue(i/d, i%d, n-1) // zero-indexed

}

}

wg.Wait()

fmt.Println(g)

}

Analysis

Sudokami solves sudoku puzzles by separating out logical inference patterns that are independent of each other and can therefore be evaluated concurrently. It does this by implementing a network of mailbox-like channels according to a communication protocol that is atypical for Go in two ways:

- Each channel has many senders and only one receiver. This would complicate matters in the event that the channels need to be closed for whatever reason, but…

- Since only the first value sent on a channel carries essential information, subsequent values don’t even need to be consumed, as long as the channels are buffered to sufficient capacity to avoid blocking.

The payoff for this unorthodox usage of Go’s concurrency primitives is the complete elimination of the need for recursion or backtracking, or indeed any kind of conjecture. And since each Candidate and Group is free to go dormant after sending a single value to its counterparts, one might suppose that this approach cuts down on some of the wasted cycles that a single-routine iterative algorithm might go through, except that this is achieved by essentially foisting much of the algorithmic complexity onto the runtime itself. While this is precisely one of the things the runtime is designed for, introducing high-level concurrency structures into an application that does not require them can be expected to compromise performance. In this case, the solution process takes about 300 µs on my machine—not counting an exorbitant 2.6 milliseconds of setup time for the call to NewGrid. Not the fastest way to solve a sudoku.

But neither is using eyes, hand, pencil, and paper. And a concurrent approach roughly mimics the way humans are most comfortable working on a puzzle: by gazing across its face and investing their mental processing power according to experience and intuition.

A next step in strengthening Sudokami would be to address its fundamental algorithmic limitation: a simplistic implementation in which Groups only communicate with Candidates, and do so without knowledge of their Candidates’ locations, can only solve the subset of puzzles that do not require any techniques beyond sole candidate inference. Puzzles involving more advanced patterns, such as hidden pairs, would require Groups to confer directly with each other and apprise each other of the status of their Candidates, which in turn requires each Group to be able to identify each of its Candidates. Communication between Groups also invalidates Sudokami’s current assumption regarding required buffer sizes, as the number of messages to be sent on each Group’s channel is no longer known. This would be a fruitful avenue for future development.